The Carolina Dog is a feral or semi feral landrace of dogs native to the South East United States, mostly in Georgia and Carolina. Commonly called the American dingo due to their similar appearance the Carolina Dog is unrelated to Austrialian Dingos. Representing a unique line of wild dogs found only in the United States.

While various groups of feral dogs are not by any means uncommon in the American South and have existed for hundreds of years, likely long before the arrival of European settlers. The author himself recalls many packs of feral dogs in rural areas of Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas and Oklahoma. These dogs are typically descended of strays, usually rely on human settlements for food and are often thought of as pests no different then the feral pigs that are so common in the same areas.

These dogs tend to run in packs and come from a variety of breeds but overtime some groups will start to become more genetically isolated and form a “landrace”. Where the dogs in a given area will become more genetically similar, exhibiting a common set of physical characteristics and behaviors. These landraces of wild dogs often don’t last long as they’re often exterminated or removed as pests. Genetic admixture from other dog lines prevents them from maintaining the genetic isolation necessary to maintain shared characteristics.

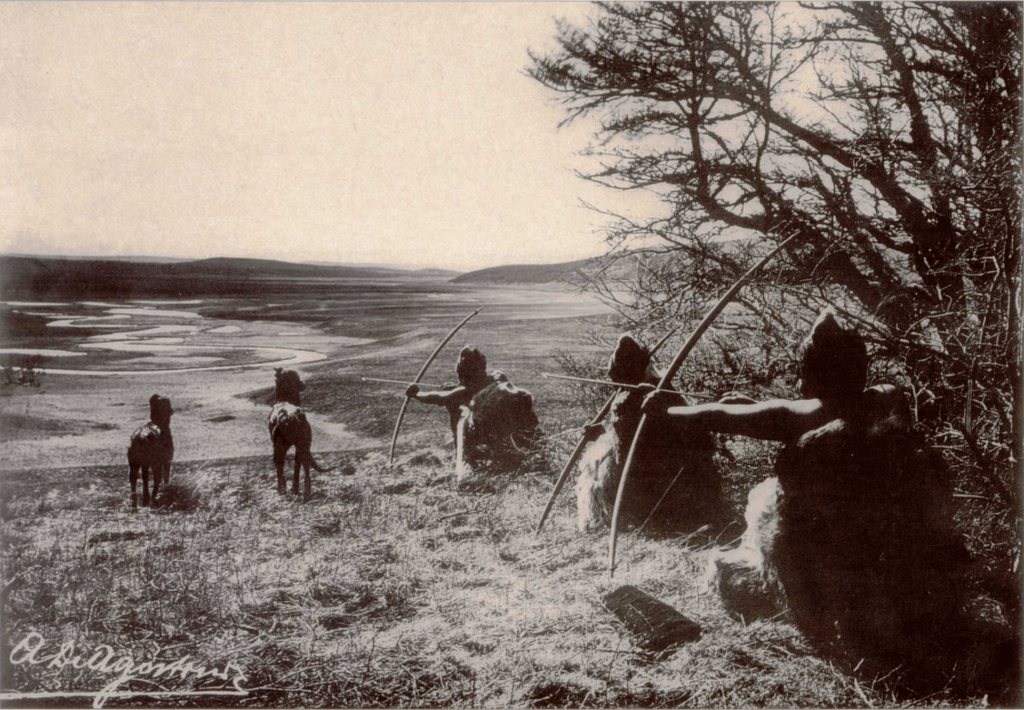

What makes the modern Carolina dog is unique due to a large portion of their genetic makeup being from the dogs used by Indigenous people of the South Eastern United States. As well as their ability to survive in remote areas without reliance on human settlement to supply them with food. (Brisbin and Risch, 1997)

Historically these dogs were often referred to as “Indian dogs” or aboriginal dogs (Cope 1863). Not much thought was given by ethnologists and biologists to these dogs until Dr. I. Lehr Brisbin lead ecologist of University of Georgia’s Savannah River Ecology Laboratory which studies the area around the Savannah River Nuclear Site. This site covers 310 square miles, area is almost completely depopulated and sealed off from trespassers which has allowed the Carolina dog to thrive (Brisbin and Risch, 1997).

They survive by hunting small to medium prey including shrews, raccoons, mice and reptiles with a tendency to pounce on prey like a fox. Reproductively the Carolina dog exhibits three successive estrus cycles which often settle into seasonal patterns when there’s an abundance of puppies. It is thought that this quick breeding enables Carolina dogs to reproduce quickly enough to sustain their population in the face of diseases, parasites and other challenges of living in the wild. Male Carolina dogs have also been observed to stay with their puppies and play a more active role then other dogs (Primitive Dogs).

In regards to DNA there have been mixed results. One 2013 study on mitochondrial DNA indicated that 37% carried a unique haplotype (A184), which had not been previously documented and is related to the a5 mtDNA sub-haplogroup that came from East Asia (Boyko and vonHoldt).

Another study in 2018 included three individual Carolina dogs showed a 0%-33% admixture from pre-Columbian dogs or from Arctic dogs. The study had no available method to identify the difference between these two groups and with only three dogs tested more research is certainly necessary to access the true genetic origins of this unique American dog. As a result some researchers believe that it may not have any pre-Columbian Dog DNA but the unique (A184) haplotype makes this seem unlikely. (Ní Leathlobhair et al. 81)

Works Cited

Ní Leathlobhair, Máire, et al. “The Evolutionary History of Dogs in the Americas.” Science, vol. 361, no. 6397, 2018, pp. 81–85. PubMed Central, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7116273/. Accessed 15 Dec. 2024.

Boyko, Adam R., and Bridgett M. vonHoldt. “Canid Domestication and Population Genomics.” PLOS Genetics, Public Library of Science, 8(8), Aug. 2012, doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002892. Accessed 15 Dec. 2024.

Primitive Dogs Team. “Carolina Dog Breed Info and Characteristics.” Primitive Dogs, Primitive Dogs, https://primitivedogs.com/carolina-dog-breed-info-characteristics/. Accessed 15 Dec. 2024.

Cope, E. D. Dogs of the American Aborigines. 1863. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/cbarchive_107744_dogsofamericanaborigines1863/page/n183/mode/2up. Accessed 15 Dec. 2024.

“Carolina Dog.” Wikipedia, 15 Dec. 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carolina_Dog. Accessed 15 Dec. 2024.

Brisbin, Ian L., and Thomas S. Risch. “Primitive Dogs, Their Ecology and Behavior: Unique Opportunities to Study the Early Development of the Human-Canine Bond.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, May 1997, doi:10.2460/javma.1997.210.8.1122a. Accessed via ResearchGate.

Tim the Historian. “The American Dingo: Carolina Dogs~ History from Home.” YouTube, 30 Apr. 2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=gwNc9wIO2M4. Accessed 15 Dec. 2024.

4o